I. New York to Oakland

A letter to brother David: Mar 3, 1868

...I start for California weeds and trees next Thursday on the steamship Santiago de Cuba. My health has improved since the cool winds of Cape Hatteras and Sandy Hook have fanned me. I will soon be able for long walks again, and work.

Business is dull in New York. I suppose it is brisk in Portage. I intended to visit Barnum's museum, but it was burned last night. My love to all. I will hope to hear from you and mother and the girls at San Francisco. I rec'd your $150. package at Havana. Once more adieu,

John Muir

A letter to brother David: July 14, 1868

On the Merced River near Snelling, Merced Co., Cal., July 14th, [1868].

Dear Bro. David,

I have lived under the sunny sky of California nearly 3½ months, but have not yet rec'd a single letter from any source-perhaps a few went to the dead letter off[ice] while I was in the mountains, but I am settled now with a ranchman for eight or nine months, and hope to enjoy a full share of the comfort of letters during my long isolation.

A letter to the Merrills: July 19, 1868

Hopeton, Merced Co., California

At a farm-house near Snelling on Merced River, California. July 19, [1868]

To Miss Catherine, and Miss Mina and Mrs Moores, and to all of the genus Merrill, my most cordial greeting;

I do wish I could see you all. Our world has gone more than half way 'round the sun since I heard from and of you, I am lonesome. I have not received a single letter from anyone since my departure from Florida, but I mean to settle here for a few months, and hope to see this big gap in tidings from friends well mended.Flowers and fate have carried me to California, and I have reveled and luxuriated in its mountains and plants and bright sky for more than a hundred days, and were it not for a thought now and then of isolation and loneliness, the happiness of my existence. I saw but little of the tropical grandeur of Panama, for my health was still in wreck, and I did not venture to wait the arrival of another steamer, so I had only half a day to collect specimens- the isthmus train moved with cruel speed, and I could only gaze from the car platform, and weep and pray that the Lord would some day give me strength to see it better.

The scenery of the ocean is intensely interesting, very far exceeding in beauty and magnificence the highest of my most ardent conceptions. I arrived in San Francisco about the first of Apr. and struck out at once to the country.

A letter to Mrs. Carr: July 26, 1868

Near Snelling, Merced Co., California, July 26th, [1868.]

I have had the pleasure of but one letter since leaving home from you. That I received at Gainesville, Georgia. I have not received a letter from any source since leaving Florida, and of course I am very lonesome and hunger terribly for the communion of friends. I will remain here eight or nine months and hope to hear from all my friends.

Fate and flowers have carried me to California, and I have reveled and luxuriated amid its plants and mountains nearly four months. I am well again, I came to life in the cool winds and crystal waters of the mountains, and, were it not for a thought now and then of loneliness and isolation, the pleasure of my existence would be complete. I have forgotten whether I wrote you from Cuba or not. I spent four happy weeks there in January and February.

I saw only a very little of the grandeur of Panama, for my health was still in wreck, and I did not venture to wait the arrival of another steamer. I had but half a day to collect specimens. The Isthmus train rushed on with camel speed through the gorgeous Eden of vines and palms, and I could only gaze from the car platform and weep and pray that the Lord would some day give me strength to see it better.

After a delightful sail among the scenery of the sea I arrived in San Francisco in April and struck out at once into the country.

A letter to "twin Ann": Aug 15, '68:

Hopeton, Aug. 15 '68

Dear twin Ann,

I was sorry to know that you had borrowed trouble over me, your anxiety was of far too rapid a growth, having sprouted, leafed, and fruited ere it had any business to come out of the ground.

Those three months in which I was reported missing were the floweriest of all the months of my existence, no matter what direction I traveled I still waded in flowers by day, and slept with them by night, hundred of flowery gems of most surpassing loveliness touched my feet at every step, and buried them out of sight. I was very happy, the larks and insects sang streams of unmeasured joy, - glorious mountain walls around me, -- a sky of plants beneath, and a sky of light above all kept by their Maker in perfect beauty and pure as heaven.

I am always a little lonesome, Annie. Ought I not to be a man by this time and put away childish things. I have wandered far enough, and seen strange faces enough to feel the whole world a home, and I am a batchelor too. I should not be a boy, but I cannot accustom myself to the coldness of strangers, nor to the shiftings and wanderings of this Arab life.

Rambles of a Botanist: 1872

...On the second day of April, 1868, I left San Francisco for Yosemite Valley, companioned by a young Englishman. Our orthodox route of "nearest and quickest" was by steam to Stockton, thence by stage to Coulterville or Mariposa, and the remainder of the way over the mountains on horseback. But we had plenty of time, and proposed drifting leisurely mountainward, via the valley of San Jose, Pacheco Pass, and the plain of San Joaquin, and thence to Yosemite by any road that we chanced to find; enjoying the flowers and light, "camping out" in our blankets wherever overtaken by night, and paying very little compliance to roads or times. Accordingly, we crossed "the Bay" by the Oakland ferry...

Pelican Bay Manuscript: 1907

[written in1907, Pelican Bay, Klamath Lake, Oregon, while visiting railroad magnate Edward Harriman. Part of this manuscript became "Story of my Boyhood and Youth"]

.I thought that I would postpone my South American trip and go to California to see Yosemite and the big trees and the vegetation in general. Accordingly, going to New York on a schooner loaded with oranges I there took passage on a steamer sailing for Panama, and crossed the Isthmus and arrived in San Francisco in April; stayed one day in San Francisco and then enquired of a man who was carrying carpenter's tools the nearest way out of town to the uncultivated wild part of the State. He in wonder asked "Where do you wish to go?" and I said "anywhere that is wild"; so he directed me to the Oakland Ferry and talk me to cross the Bay there, and said that that would be as good a way out of town as any. Leaving the train at East Oakland I took the first road I came to and walked up the Santa Clara Valley. The Oakland hills at this time (April) after a very rainy season were covered with flowers- patches of yellow and blue and white in endless variety made the slopes of the hills seem like a brilliant piece of patch-work.

The Yosemite: 1911

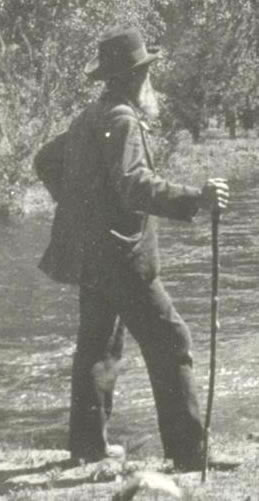

When I set out on the long excursion that finally led to California I wandered afoot and alone, from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico, with a plant-press on my back, holding a generally southward course, like the birds when they are going from summer to winter. From the west coast of Florida I crossed the gulf to Cuba, enjoyed the rich tropical flora there for a few months, intending to go thence to the north end of South America, make my way through the woods to the headwaters of the Amazon, and float down that grand river to the ocean. But I was unable to find a ship bound for South America--fortunately perhaps, for I had incredibly little money for so long a trip and had not yet fully recovered from a fever caught in the Florida swamps. Therefore I decided to visit California for a year or two to see its wonderful flora and the famous Yosemite Valley. All the world was before me and every day was a holiday, so it did not seem important to which one of the world's wildernesses I first should wander.

Arriving by the Panama steamer, I stopped one day in San Francisco and then inquired for the nearest way out of town. "But where do you want to go?" asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. "To any place that is wild," I said. This reply startled him. He seemed to fear I might be crazy and therefore the sooner I was out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry.

1000 mile walk: 1916

The day before the sailing of the Panama ship I bought a pocket map of California and allowed myself to be persuaded to buy a dozen large maps, mounted on rollers, with a map of the world on one side and the United States on the other. In vain I said I had no use for them. "But surely you want to make money in California, don't you? Everything out there is verydear. We'll sell you a dozen of these fine maps for two dollars each and you can easily sell them in California for ten dollars apiece." I foolishly allowed myself to be persuaded. The maps made a very large, awkward bundle, but fortunately it was the only baggage I had except my little plant press and a small bag. I laid them in my berth in the steerage, for they were too large to be stolen and concealed.

There was a savage contrast between life in the steerage and my fine home on the little ship fruiter. Never before had I seen such a barbarous mob, especially at meals. Arrived at Aspinwall-Colon, we had half a day to ramble about before starting across the Isthmus. Never shall I forget the glorious flora, especially for the first fifteen or twenty miles along the Chagres River. The riotous exuberance of great forest trees, glowing in purple, red, and yellow flowers, far surpassed anything I had ever seen, especially of flowering trees, either in Florida or Cuba. I gazed from the car-platform enchanted. I fairly cried for joy and hoped that sometime I should be able to return and enjoy and study this most glorious of forests to my heart's content. We reached San Francisco about the first of April, and I remained there only one day, before starting for Yosemite Valley.

Life and Letters of John Muir, William Frederic Bade: 1924

The North American Company at this time had ordered from New York a new steamship for its Pacific Coast traffic. This was the Nebraska, and she had sailed early m January, 1868, on her long maiden voyage around Cape Horn. Muir found that the Santiago de Cuba was scheduled to sail for Aspinwall on the 6th of March, and that her passengers would connect with the northward-bound Nebraska on the Pacific side of the Isthmus of Panama in about ten days. The records show that the Santiago de Cuba, not a large boat, carried on this trip four hundred passengers and five hundred and forty-two tons of freight. So overcrowded was the vessel that many passengers had to sleep on the decks. Nevertheless Muir engaged steerage passage on this boat and made connections with the Nebraska.

Son of the Wilderness, by Linnie Marsh Wolfe: 1946

About mid-February he was on an orange steamer en route for New York, clinging to a mast on deck while the storms that raged off Cape Hatteras beat upon him and cooled his blood. On March 10 he sailed for Aspinwall and the Isthmus on his way to "California's weeds and flowers." His steerage accommodations in a ship jammed to the gunwales with humanity did not afford him a pleasant voyage. Loathe always to dwell upon hardships, he could never be induced to talk about it. His journal dismisses it with the single comment: "Never had I seen such a barbarous mob, especially at meals."

On the morning of March 28, 1868 John Muir landed on the San Francisco wharf. With him was a globe-trotting cockney named Chilwell, who had agreed to go with him to the mountains. As they walked up Market Street, Muir saw nothing but the ugliness of commercialism. Stopping a carpenter with a kit of tools, he asked where he could find the quickest way out of the city, "But where do you want to go?" asked the man, "Anywhere that is wild," said Muir. "He seemed to fear that I might be crazy, and that .the sooner I got out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry."

Exultant at being now "on the wild side of the continent," Muir with his companion was soon tramping southward from Oakland among the green, rounded, oak-clothed hills toward the Santa Clara Valley.