V. Foothills

A letter to bro David: July 1868:

I had a week or two of fever before leaving the plains for Yo Semite, but it was not severe, and I was only laid up three or four days, and a month in the Sierras cooled with mountain winds and delicious crystal water has effected a complete cure.

A letter to Mrs Carr: Nov 1868:

After riding for two days in this autumn I found summer again in the higher foothills. Flower petals were spread confidingly open, the grasses waved their branches all bright and gay in the colors of healthy prime, and the winds and streams were cool. Forty or fifty miles further into the mountains, I came to spring. The leaves on the oak were small and drooping, and they still retained their first tintings of crimson and purple, and the wrinkles of their bud folds were distinct as if newly opened, and all along the rims of cool brooks and mild sloping places thousands of gentle mountain flowers were tasting life for the first time.

Letter to Mrs Carr: May 1869

Last May I made the trip on horseback, going by Coulterville and returning by Mariposa. A passable carriage-road reached about twelve miles beyond Coulterville; the rest of the distance to the valley was crossed only by a narrow trail.

Rambles of a Botanist: 1872

After travelling two days among the delightful death of this sunny winter, we came to another summer in the Sierra foothills. Flowers were spread confidingly open, and streams and winds were cool. Above Coulterville, forty or fifty miles farther in the mountains, we came to spring. The leaves of the mountain-oaks were small and drooping, and still wore their first tintings of crimson and purple; and the wrinkles of their bud-folds were still distinct, as if newly opened; and, scattered over banks and sunny slopes, thousands of gentle plants were tasting life for the first time. A few miles farther, on the Pilot Peak ridge, we came to the edge of a winter. Few growing leaves were to be seen; the highest and youngest of the lilies and spring violets were far below; winter scales were still wrapt close on the buds of dwarf oaks and hazels. The great sugar-pines waved their long arms, as if about to speak; and we soon were in deep snow. After we had reached the highest part of the ridge, clouds began to gather, storm-winds swept the forest, and snow began to fall thick and blinding. Fortunately, we reached a sort of shingle cabin at Crane Flat, where we sheltered until the next day. Thus, in less than a week from the hot autumn of San Joaquin, we were struggling in a bewildering storm of mountain winter. This was on or about May 20, at an elevation of six thousand one hundred and thirty feet. Here the forest is magnificent, composed in part of the sugar-pine (Pinus lambertiana), which is the king of all pines, most noble in manners and language. Many specimens are over two hundred feet in height, and eight to ten in diameter, fresh and sound as the sun which made them. The yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa) also grows here, and cedar (Libocedrus decurrens); but the bulk of the forest is made up of the two silver firs (Picea grandis and Picea amabilis), the former always greatly predominating at this altitude…

Pelican Bay Manuscript: 1907

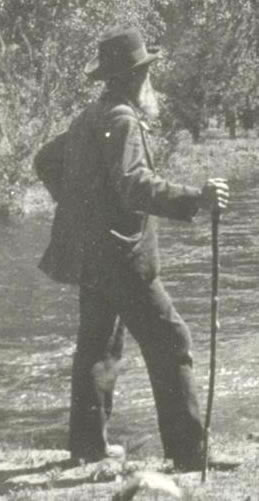

…descended the foothills by way of Colterville. This part of my journey I accompanied by a young Englishman by the name of Chilwell, a most amusing companion. We had several accidents and adventures. At Colterville in the foothills while purchasing provisions we were advised by an Italian merchant to buy an Army musket for protection against bears. Our bill of far in our camps was simple - tea and cakes, the latter toasted on the coals - made from flour without any leaven - and of course we shunned hotels in the valley, seldom indulging even in crackers, as being too costly. The cost of the entire trip of nearly a month was only about three dollars each. Chilwell, being an Englishman, loudly lamented being compelled to live on flour and water, as he expressed it, and hungered for flesh; there fore he made desperate efforts to shoot something to eat - quail, etcetera, and grouse, etcetera, but he was invariably unsuccessful - a poor shot - and declared the gun was of no use. I told him I thought that was a good gun if properly loaded and properly aimed; that at the first camp we make after his many failures I would show him how to load the gun and how to shoot. Accordingly when we had reached a height of six thousand feet, where the mountains were covered with snow about six or eight feet deep we came to a place called Crane Flat, where there we a small shake shanty, I loaded the gun, paced off thirty yards from the cabin, or shanty, and told Mr. Chilwell to pin a piece of paper on the wall and see if I could not put shot into it and prove the value of the gun. Accordingly Mr. Chilwell pinned on a piece of an envelope, vanished around the corner of the shanty, calling out "Fire away". I supposed that he had gone way back of the cabin, but instead he went inside of the cabin and stood up against the mark that he had himself place on the wall, and as the shake wall was only about half an inch thick, the shot passed through and into his shoulder. He came out, crying in great concern that I had shot him, The weather being cold, he had on three coats and as many shirts, I discovered that the shot had passed through all this clothing and the pellets were imbedded beneath the skin and had to be picked out bay the point of a pen knife. I said: "Why did you stand against that mark?" He said: "Well, I never thought that the shot would go through the 'ouse". After spending eight or ten days in visiting the great falls and other points around the valley, we made the return trip by way of Wawona, then owned by Gailand Clark, the Yosemite pioneer, From him we procured a fresh supply of flour and also some bear meat, which we tasted for the first time, and it was eagerly eaten by the Englishman…

Life and Letters: 1924

…Our bill of fare in camps was simple--tea and cakes, the latter made from flour without leaven and toasted on the coals--and of course we shunned hotels in the valley, seldom indulging even in crackers, as being too expensive. Chilwell, being an Englishman, loudly lamented being compelled to live on so light a diet, flour and water, as he expressed it, and hungered for flesh; therefore he made desperate efforts to shoot something to eat, particularly quails and grouse, but he was invariably unsuccessful and declared the gun was worthless. I told him I thought that it was good enough if properly loaded and aimed, though perhaps sighted too high, and promised to show him at the first opportunity how to load and shoot.

Many of the herbaceous plants of the flowing foothills were the same as those of the plain and had already gone to seed and withered. But at a height of one thousand feet or so we found many of the lily family blooming in all their glory, the Calochortus especially, a charming genus like European tulips, but finer, and many species of two new shrubs--especially, Ceanothus and Adenostoma. The oaks, beautiful trees with blue foliage and white bark, forming open groves, gave a fine park effect. Higher, we met the first of the pines, with long gray foliage, large stout cones, and wide-spreading heads like palms. Then yellow pines, growing gradually more abundant as we ascended. At Bower Cave on the north fork of the Merced the streams were fringed with willows and azalea, ferns, flowering dogwood, etc. Here, too, we enjoyed the strange beauty of the Cave in a limestone hill.

At Deer Flat the wagon-road ended in a trail which we traced up the side of the dividing ridge parallel to the Merced and Tuolumne to Crane Flat, lying at a height of six thousand feet, where we found a noble forest of sugar pine, silver fir, libocedrus, Douglas spruce, the first of the noble Sierra forests, the noblest coniferous forests in the world, towering in all their unspoiled beauty and grandeur around a sunny, gently sloping meadow. Here, too, we got into the heavy winter snow--a fine change from the burning foothills and plains.

Some mountaineer had tried to establish a claim to the Flat by building a little cabin of sugar pine shakes, and though we had arrived early in the afternoon I decided to camp here for the night as the trail was buried in the snow which was about six feet deep, and I wanted to examine the topography and plan our course. Chilwell cleared away the snow from the door and floor of the cabin, and made a bed in it of boughs of fernlike silver fir, though I urged the same sort of bed made under the trees on the snow. But he had the house habit.

After camp arrangements were made he reminded me of my promise about the gun, hoping eagerly for improvement of our bill of fare, however slight. Accordingly I loaded the gun, paced off thirty yards from the cabin, or shanty, and told Mr. Chilwell to pin a piece of paper on the wall and see if I could not put shot into it and prove the gun's worth. So he pinned a piece on the shanty wall and vanished around the corner, calling out, "Fire away."

I supposed that he had gone some distance back of the cabin, but instead he went inside of it and stood up against the mark that he had himself placed on the wall, and as the shake wall of soft sugar pine was only about half an inch thick, the shot passed through it and into his chowder. He came rushing: out, with his hand on his chowder, crying in great concern, "You've shot me, you've shot me, Scottie." The weather being cold, he fortunately had on three coats and as many shirts. One of the coats was a heavy English overcoat. I discovered that the shot had passed through all this clothing and into his shoulder, and the embedded pellets had to be picked out with the point of a penknife. I asked him how he could be so foolish as to stand opposite the mark. "Because," he replied, "I never imagined the blank gun would shoot through the side of the 'ouse." …